In an exchange of essays on American democracy published in the January 11, 1941, issue of The Nation, a few leading intellectuals of the time explored the question “Who owns the future?” The context: an escalating world war and the rise of fascism and despotism, which had engulfed the world in an ideology that would cost millions of lives. The tension in the debate is one that has existed throughout history: Can we remake the world in a way that generates a future full of opportunities and possibilities for the majority? In one piece, Professor Frederick Schuman, predicting the demise of democracy, posited that Americans were too weak in spirit and shallow in thinking—too “decadent”—to stop the march of what he called “Caesarism.” He argued that “this is not a defect of our collective power. It is a defect of our collective wisdom and our collective will.” Schuman passed off his cynical worldview as high-minded intellectualism, but The Nation’s editors—along with Max Lerner, in a spirited rebuttal—saw his argument for what it was: the bitter resignation of an “intellectual defeatist.” Schuman, like many others in those very dark days, had lost faith in the power and promise of citizenship in a participatory democracy.

Beginning in the late 1970s, another assault was under way, this one more clever and in some ways more lasting. A movement centered around Ronald Reagan ratcheted up the belief that the individual is paramount. The notion of collective provision, compassion and citizenship was replaced by consumerism and greed as a way to “participate” in society and define who we are. Using a linguistic attack wrapped in the language of freedom, Reaganism made individualism seem selfless, even heroic, while the idea of government obligation to help the needy was seen as vain or wasteful. Cynicism was the engine driving this new political and cultural outlook. It was a time when the free market—not democracy—was put forth as the answer to our problems. Corporations would now be more powerful than governments. Reagan’s partner across the pond, Margaret Thatcher, succinctly summed up this dangerous mythology when she said, “There is no such thing as society, only individuals and families.”

Despite the theatrics depicting Reagan and Thatcher as bold, gutsy leaders, each presented a fantasy of purity, simplicity and security while rejecting the notion that there were serious internal problems to address. Everything was just right, because Western individualism had defeated fascism and would soon defeat communism. All we needed to do was return to an idyllic past—one that never really existed. “It’s morning in America,” announced the famous Reagan campaign ad, ignoring the obvious question: Morning for whom? Reagan and Thatcher wanted us to forget about last night by using fear (the threat of nuclear war) and cynicism (their way was the only way; no alternative) to convince us that change was risky or impossible. In their effort to promote a new brand of individualism, they tried to establish a thoughtless conformity that bred submissiveness and an ahistorical consciousness. Together, they set about erasing history by attempting to roll back the gains of the New Deal and Great Society (here) and the social democratic state (in Britain).

All of it served to pull us apart, placing “I” above “we.”

As the adolescent son of Italian immigrants (a bricklayer father, a cafeteria worker mother), I couldn’t relate to Reaganism. It contradicted the core elements of how my family survived: sharing, working together and looking out for one another. It led me to ask what we could do in the face of such absurdity. The question still burns a hole in my head and in my heart.

“You’re automatically part of society.” These words from my father still echo in my memory twenty-five years after his death. Born in the Italian mountain village of Colli a Volturno in 1941, only a few months after that Nation issue hit the newsstands, he lived the early part of his life underground, his mother desperately trying to keep her youngest child alive as Italy was collapsing under the rule of Mussolini, war, occupation and despair. I knew his struggle, so his words always went deeper for me, meant something more. Working with him starting at the age of 7 as a part-time laborer and full-time translator, I listened, watched, and sometimes interpreted the ideas and conversations that he and his fellow skilled tradesmen (many of them immigrants) had as they recast obstacles into opportunities. They had to work together, overcoming inclement weather, bungled architectural blueprints and unrealistic building deadlines set by developers looking for quick turnarounds. Witnessing the way they moved through life inspired in me an awareness I describe as “creative response.”

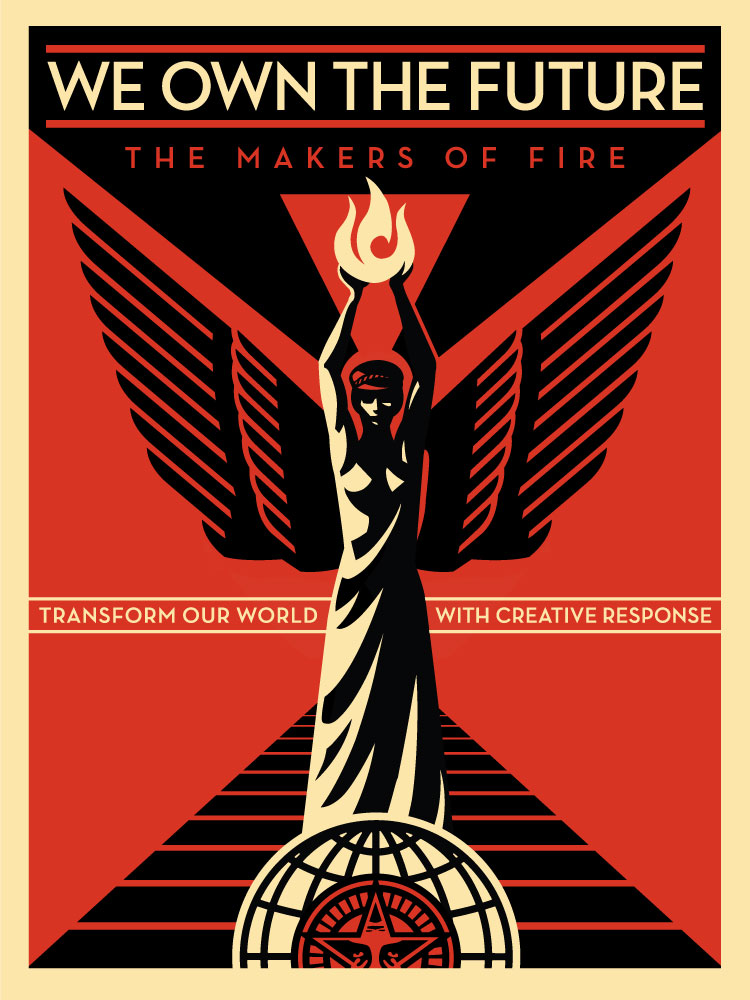

We’re all agents of history, curators of our evolving humanity. That’s the sentiment radiating from my film Let Fury Have the Hour. It inspired this special issue of The Nation that I guest-edited, including the contributions that follow this essay from artists, activists and writers who appear in my film, as well as the cover art by Shepard Fairey. And it’s an allegorical expression of what I feel when I look at Swiss painter Paul Klee’s 1920 etching Angelus Novus (Angel of History), a creative-response touchstone for me. Philosopher Walter Benjamin described Klee’s Angel with its back to the future, desperate to alter a past shattered by the reactionary, explaining: “This is how one pictures the angel of history…. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed.” Klee’s painting is an intrepid exploration of the historical and artistic imagination, embracing the disarray of the past and reorganizing the chaos of the present, all in the service of shaping a future where the world works for everyone. “Art does not reproduce what we see; rather, it makes us see,” Klee explained. His masterwork refuses anything that suppresses human possibility, answering the Reagans and Thatchers throughout history: “We own the future.”

For me, creative response is the antidote to the individualism, consumerism and cynicism that now define our culture. I first discovered its expression through punk music, which gave me the permission to yell out what I believed. Next it was skateboarding, which recalibrated the physical world through something as simple as a piece of wood and urethane wheels. Later, street art offered a direct form of free expression—a true public gallery obliterating the barrier between my fellow global citizens and me. Finally, early rap mixed what was floating in and around popular culture into a potent, unique language that still speaks to me.

Creative response sent me on a journey, uncovering the work of many artists and thinkers throughout history who asked the same question. From Picasso’s moving antiwar testimonial (Guernica) to Miriam Makeba’s songs for equality and freedom (The Voice of Africa), from Stephen Jay Gould’s fight against pseudosciences that advance racism and sexism (The Mismeasure of Man) and Italian playwright Dario Fo’s popular theater (Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay!) to the social satire of Richard Pryor and the protest dub poetry of Linton Kwesi Johnson, all defied the claim that we must accept conditions as they are. In our new millennium, there are many who give us new songs to sing and stories to tell, new images to find our reflection in, new ways to organize our ideas. They include Iranian artist Morehshin Allahyari, Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Zimbabwean musicians the Abangqobi Group, Russian punk band Pussy Riot and Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, who despite exile, suppression, detention or worse use creative response as a timely and timeless endeavor to make the world work better for everyone. In essence, what Schuman criticized as a deficit in that 1941 Nation essay is something we actually hold in deep reserve. Our collective mind is an expression of the human spirit, and we must always find and embrace new ways to release it.

Ai Weiwei and Pussy Riot present two profound examples. In the wake of the 2008 earthquake that devastated Sichuan Province, killing nearly 70,000, it was revealed that 7,000 schoolrooms had collapsed due to poor engineering and substandard construction—a fact the Chinese government foolishly tried to cover up. Bypassing China’s media censors, Ai posted daily the names of students who had died in the quake, using social media through proxy servers hosted by supporters around the world. He amplified his outrage via Twitter (one of the first and most prominent uses of that platform). Ai’s expressions of sorrow quickly generated support from millions around the world and galvanized the Chinese people. The government, faced with growing public outrage, had no choice but to offer the grieving parents an opportunity to seek justice. Ai’s continued exposure of China’s corruption and human rights abuses led to his detention. He was released in 2011, but instead of fleeing China, Ai stayed and continues to shine a spotlight on his country’s struggles, explaining: “Your own acts and behavior tell the world who you are and at the same time what kind of society you think it should be…. Liberty is about our rights to question everything.”

In Pussy Riot’s case, the jailing of three of its members last year was the unjust outcome of the group’s courageous performance in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Savior to protest the Orthodox Church’s support for repressive Russian President Vladimir Putin. It resulted in a music video that angered and embarrassed Putin and conservative church leaders. Ultimately, three members of Pussy Riot were sentenced to two years in prison for “hooliganism” (one was released on parole). Putin declared that the musicians “undermine the moral foundation” of the country, while international groups like Amnesty International designated the women prisoners of conscience. “We were looking for authentic genuineness and simplicity, and we found them in the holy foolishness of our punk performances,” Nadezhda Tolokonnikova said in her closing statement at trial. “Passion, openness and naïveté are superior to hypocrisy, cunning and a contrived decency that conceals crimes. The state’s leaders stand with saintly expressions in church but, in their deceit, their sins are far greater than ours.” Connecting the two actions are Ai’s words: “Imagine one day, the hateful world around you collapses. And it is your attitude, words and actions that put an end to it. Will you be excited?”

As the examples of Ai Weiwei and Pussy Riot demonstrate, creative response can shift how we think, how we see; it leads us to feel something different about our experience and the world. It advances the odd, the idiosyncratic, the impossible; its elusiveness is both anti-ideological and universal as it rallies us around our common humanity. It compels us to take an active participation in the world by challenging the destructive ideologies—corporate hegemony, mass media dominance, jingoism and cultural chauvinism—that corrupt our society. It can generate inventive actions in every area of society, from technology (the open-source collective Protei), economics (the Basque region of Spain’s Mondragon cooperative) and science (physicist Brian Greene’s topology change) to public health (Mozambique’s Estamos) and sports (Germany’s anti-commercial soccer club St. Pauli), from architecture and housing (Estudio BaBO’s earthquake-safe CFL row houses in Argentina) to the environment (New Mexico’s New Energy Economy) and public service (Burma’s Aung San Suu Kyi). All are connected with a sensibility that art—or, more specifically, creative response—is something we do, in answer to the question “What kind of world do you want to live in?”

Ultimately, creative response insists that each of us maintain the courage of our convictions to meet the extraordinary challenges that confront our world. It’s this spirit that answers the question “Who owns the future?” The new, emerging “we” own the future: because our rejection of cynicism and apathy free us from the trap of history’s bad ideologies; because embracing compassion as a cornerstone of democracy allows us to imagine ourselves in the position of another; because transforming the narrow thinking of the past and problems of the present opens up possibilities for the future; and because the moment we see ourselves as citizens of the world, the future is ours.

Original article: How creative response artists and activists can transform world