“Frank Serpico” is a finely etched and fascinating documentary. Directed by Antonino D’Ambrosio, it’s a portrait of the legendary Brooklyn-born Italian- American cop who blew the whistle on New York police corruption in the late ’60s and early ’70s — and, of course, it’s a movie you can hardly watch without comparing it to “Serpico,” the 1973 Sidney Lumet drama, starring Al Pacino in the title role, that became a classic of New Hollywood street grit and moral urgency.

“Frank Serpico” is a finely etched and fascinating documentary. Directed by Antonino D’Ambrosio, it’s a portrait of the legendary Brooklyn-born Italian- American cop who blew the whistle on New York police corruption in the late ’60s and early ’70s — and, of course, it’s a movie you can hardly watch without comparing it to “Serpico,” the 1973 Sidney Lumet drama, starring Al Pacino in the title role, that became a classic of New Hollywood street grit and moral urgency.

How accurate was “Serpico”? The short answer is: very. It stuck close to the 1973 Peter Maas book, and “Frank Serpico” reveals just how much of Serpico’s story became, through the movie, iconic. As it turns out, the legend and the truth match up nicely.

As you watch “Frank Serpico,” the story comes rushing back, and it now seems all the more amazing, like a Western that really happened. The idealistic uniformed cop of the early ’60s who recoiled at bribes the moment they were first offered to him. (Taking money was something he felt allergic to.) The upstart hippie detective, in his long hair and sandals, who started to live in Greenwich Village — where, as we learn, it took about five minutes for his neighbors to figure out that he was a cop. The giant sheepdog. The way that everyone called Frank “Paco.” The police brass who listened sympathetically to his complaints about corruption and did next to nothing. His assignment to the brutal narcotics division (his punishment), where his fellow cops all hated him. And then…

The fateful night of Feb. 3, 1971, when Serpico got shot in the face while leading a drug bust in Williamsburg, an incident widely believed to have been a set-up. (Three months later, the New York magazine cover that launched his fame read, “Portrait of an Honest Cop: Target for an Attack,” with a line that added, “Not everyone was glad it didn’t kill him.”) The formation of the Knapp Commission, which happened because of Serpico. His testimony before it, after which he disappeared to Europe.

Lumet and company got almost all of this right, though as “Frank Serpico” reveals, a telling incident occurred early on during the filming in which Serpico himself, on set, watched the scene where racist cops shove an African-American man’s face into a toilet, and he yelled “Cut!” His objection was that it never happened. Lumet banned him from the set, yet the incident was pure Serpico. He was a purist who couldn’t have been less interested in distorting the truth.

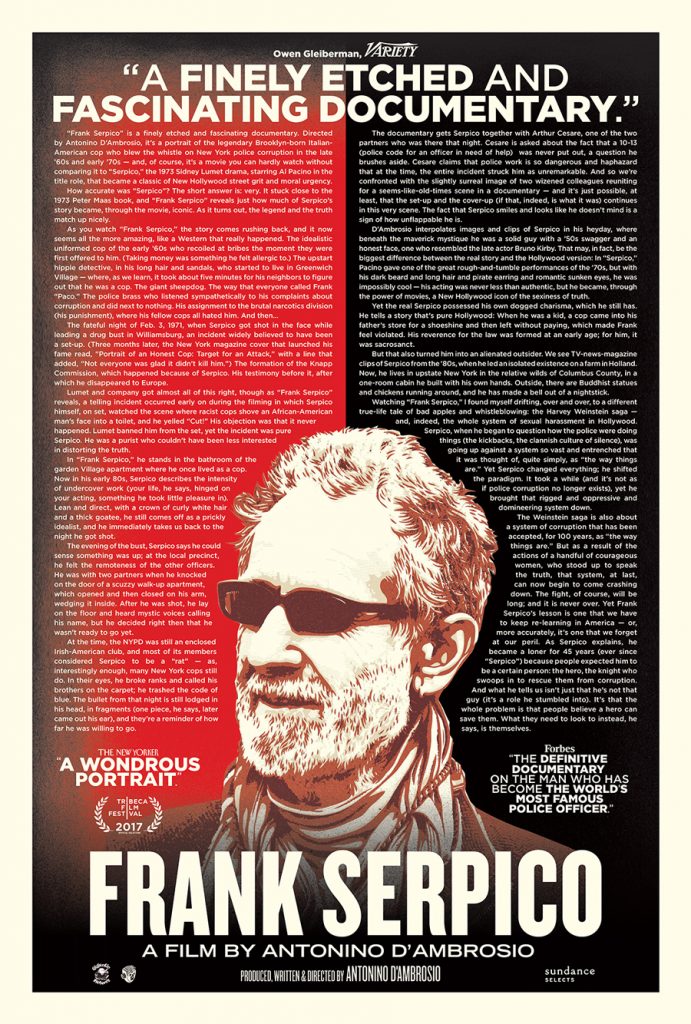

In “Frank Serpico,” he stands in the bathroom of the garden Village apartment where he once lived as a cop. Now in his early 80s, Serpico describes the intensity of undercover work (your life, he says, hinged on your acting, something he took little pleasure in). Lean and direct, with a crown of curly white hair and a thick goatee, he still comes off as a prickly idealist, and he immediately takes us back to the night he got shot.

Theeveningofthebust,Serpicosayshecould sense something was up; at the local precinct, he felt the remoteness of the other officers. He was with two partners when he knocked on the door of a scuzzy walk-up apartment, which opened and then closed on his arm, wedging it inside. After he was shot, he lay on the floor and heard mystic voices calling his name, but he decided right then that he wasn’t ready to go yet.

At the time, the NYPD was still an enclosed Irish-American club, and most of its members considered Serpico to be a “rat” — as, interestingly enough, many New York cops still do. In their eyes, he broke ranks and called his brothers on the carpet; he trashed the code of blue. The bullet from that night is still lodged in his head, in fragments (one piece, he says, later came out his ear), and they’re a reminder of how far he was willing to go.

“A WONDROUS PORTRAIT.” – The New Yorker

The documentary gets Serpico together with Arthur Cesare, one of the two partners who was there that night. Cesare is asked about the fact that a 10-13 (police code for an officer in need of help) was never put out, a question he brushes aside. Cesare claims that police work is so dangerous and haphazard that at the time, the entire incident struck him as unremarkable. And so we’re confronted with the slightly surreal image of two wizened colleagues reuniting for a seems-like-old-times scene in a documentary — and it’s just possible, at least, that the set-up and the cover-up (if that, indeed, is what it was) continues in this very scene. The fact that Serpico smiles and looks like he doesn’t mind is a sign of how unflappable he is.

D’Ambrosio interpolates images and clips of Serpico in his heyday, where beneath the maverick mystique he was a solid guy with a ’50s swagger and an honest face, one who resembled the late actor Bruno Kirby. That may, in fact, be the biggest difference between the real story and the Hollywood version: In “Serpico,” Pacino gave one of the great rough-and-tumble performances of the ’70s, but with his dark beard and long hair and pirate earring and romantic sunken eyes, he was impossibly cool — his acting was never less than authentic, but he became, through the power of movies, a New Hollywood icon of the sexiness of truth.

Yet the real Serpico possessed his own dogged charisma, which he still has. He tells a story that’s pure Hollywood: When he was a kid, a cop came into his father’s store for a shoeshine and then left without paying, which made Frank feel violated. His reverence for the law was formed at an early age; for him, it was sacrosanct.

But that also turned him into an alienated outsider. We see TV-news-magazine clips of Serpico from the ’80s, when he led an isolated existence on a farm in Holland. Now, he lives in upstate New York in the relative wilds of Columbus County, in a one-room cabin he built with his own hands. Outside, there are Buddhist statues and chickens running around, and he has made a bell out of a nightstick.

Watching “Frank Serpico,” I found myself drifting, over and over, to a different true-life tale of bad apples and whistleblowing: the Harvey Weinstein saga — and, indeed, the whole system of sexual harassment in Hollywood. Serpico, when he began to question how the police were doing things (the kickbacks, the clannish culture of silence), was going up against a system so vast and entrenched that it was thought of, quite simply, as “the way things are.” Yet Serpico changed everything; he shifted the paradigm. It took a while (and it’s not as if police corruption no longer exists), yet he brought that rigged and oppressive and domineering system down.

The Weinstein saga is also about a system of corruption that has been accepted, for 100 years, as “the way things are.” But as a result of the actions of a handful of courageous women, who stood up to speak the truth, that system, at last, can now begin to come crashing down. The fight, of course, will be long; and it is never over. Yet Frank Serpico’s lesson is one that we have to keep re-learning in America — or, more accurately, it’s one that we forget at our peril. As Serpico explains, he became a loner for 45 years (ever since “Serpico”) because people expected him to be a certain person: the hero, the knight who swoops in to rescue them from corruption. And what he tells us isn’t just that he’s not that guy (it’s a role he stumbled into). It’s that the whole problem is that people believe a hero can save them. What they need to look to instead, he says, is themselves.

Released by IFC Films Sundance Selects

Trailer: http://www.ifcfilms.com/films/frank-serpico

Watch on-demand, in select theaters and stream on Amazon and Hulu:

https://www.hulu.com/watch/1269126