All anyone needed to do was press the record button and watch. Then listen. A demand. No hesitation because he believed in songs. Hard. He believed in the promise of democracy. Hard. Johnny Cash believed. His big vision intensified by concern for the suffering of others because he never forgot his struggles to survive. It’s through Cash’s compassion his true artistry shines. It was his process and his point: to care. And never stop. He poured it all into an obscure 1964 concept record of Native American protest folksongs called Bitter Tears. Did you know Cash was a folksinger? He was. Always. Did you know Cash made concept records? He did, years before the Beatles got the credit.

This story begins in 1962. Cash crashed at Carnegie Hall and then landed in a Greenwich Village basement called the Gaslight. Onstage was little-known folksinger Peter La Farge, the first signed by John Hammond to Columbia Records. Unlike anyone,

La Farge’s folk ballads revealed a history – our history. No one noticed. Cash did. And he believed after hearing La Farge sing of Pima Indian Ira Hayes, a Marine immortalized in the famous U.S. flag-raising photo taken at the Battle of Iwo Jima which he somehow survived only to die on a reservation shattered by indifference and alcohol. La Farge’s words slammed into Cash’s self-concept forcing him to find a new breath. The one-time playwright, bronco rider, son of Pulitzer Prize-winning author Oliver La Farge told the stories of his days – our days – then, now and forever. But no one listened. Cash heard and then found his voice. Everything seemed possible.

Outside the studio walls, 1964 America was shifting from side to side, knocking history around with each movement from the Native fish-ins to the National Indian Youth Council protests. If America was a nation of laws then it was time to prove it, not by “terminating” Native sovereignty – a public policy popular at the time – but by honoring the treaties that protected it. Nothing could be the same. Cash felt it because it was a responsibility to oppose the conditions that provoke injustice. You can’t have democracy half way. What many saw as representing nothing Cash knew meant everything. These songs were everything.

As Cash swept into the Nashville Columbia Records studio in April 1964, there was a steady focus in the room. He huddled quietly with La Farge in a corner; Cash’s pockets stuffed full from hits “I Walk the Line” and “Ring of Fire” – currency paying his way to Bitter Tears. Belief. The feeling filled the air. The result, eight songs: five by La Farge and three Cash originals. Concise, brief, carefully put together: the message an unwavering grace note in history, his defiance of the times for the sake of bearing witness. Even in the breaths Cash left nothing uncertain. With the country embroiled in escalating conflicts here and abroad, is

it any wonder many refused to listen? Angered by the cowardice, Cash’s protest became a full-page Billboard ad: “Ballad of Ira Hayes” IS strong medicine. So is Rochester – Harlem – Birmingham and Vietnam… I had to fight back.” Line drawn. Time to cross. “When I read those words, it was a lesson,” Rosanne Cash says. They still are. I had to join Cash in his bold confrontation against the backsliding flow of history. The result was my book A Heartbeat and a Guitar. It inspired Masterworks’ Chuck Mitchell to make good on Cash’s promise inviting the openhearted producer Joe Henry to become the intrepid conductor of our emerging chorus.

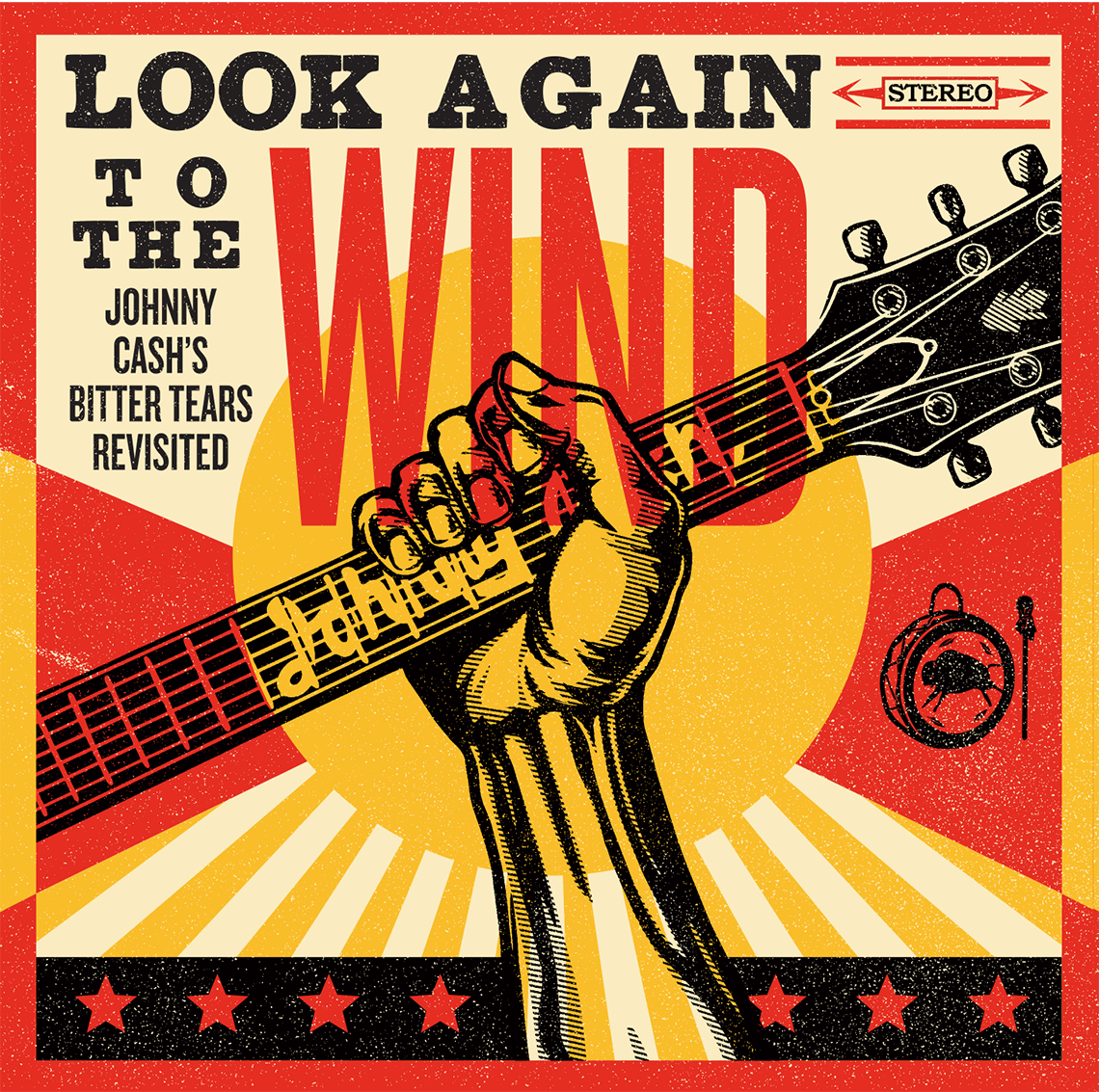

Fifty years later, we stand with a cast of inheritors accepting Cash’s demand to draw a new line. The reimagining of Bitter Tears knows everything is yet to unfold. The canvas is framed by this conviction, remaining true to the impulse of the original record but boosting its sublime quality. It extends the sonic mural Cash first painted, meant to rouse our aspirations as it pays tribute to pure survival. Just listen closely to the songs as distinct, step back to hear the whole and then slip beyond the frame to see everything. The stories rendered in each song feel real, not abstractions unconnected to our lives.

Emmylou Harris steps in and brings Cash’s grave anti-war song “Apache Tears” into the present, lamenting our current troubles of war and despair. “Of course he was a folksinger,” Harris says. “John was everything.” Cash’s longtime friend Kris Kristofferson insists we don’t forget the tale of Ira Hayes, warning us that the ghosts of those we have abandoned haunt us forever, searching for the justice that eluded them in life. Dave Rawlings and Gillian Welch take La Farge’s supreme songwriting achievement and pack it with mercy to illuminate one of our country’s saddest unknown tragedies, the government flooding of Seneca land in upstate New York – long-ago promised never to be touched by George Washington in a treaty sealed with the promise “as long as the grass shall grow.” Steve Earle pumps “Custer” full of energy, doing it as only the punk rock Voltaire can, declaring these songs are full of “empathy, a human rhythm.” The Milk Carton Kids, a folk duo who manage to seem from another era but are very much of the new millennium, push the suffering of La Farge’s “White Girl” straight into our hearts.

Then it’s the Carolina Chocolate Drops’ Rhiannon Giddens with a performance of “The Vanishing Race” so exquisite that it sears the imagination. “The fight is to get out of the stereotype that we’re gone,” Giddens says. “We’re still here.” If you don’t feel and you don’t believe after listening, then you’ve stopped breathing. Nancy Blake’s sensitive recasting of Cash’s “Talking Leaves” rep- resents the soul of the record. “People think that you don’t have a voice because you’re quiet,” Blake says about the recording. “These songs strengthen your voice.” To match Nancy Blake is Mohican musician Bill Miller. “Our people, the Indian people, the world has never truly heard our voice fully,” Miller says after recording the album’s most uplifting moment, La Farge’s “Look Again to the Wind.” “This record gives me that chance.” And then there is Norman Blake, standing next to Cash fifty years before. Here he is now brightening his friend’s humanist statement. “There are drums around the mountain and they are getting mighty near,” Blake sings in the La Farge song. He sings it not as a warning but as a message of resolute belief. These are our drums – our music – an aspiration allowing the musicians to perform the notes composed in history. Ultimately, no artist here stands in the mural’s foreground. Henry, with generosity, has shaped a record into one voice: our voice.

“A lot of people run roughshod on Native issues in Congress because they can get away with it just like they did with the Seneca and Tuscarora.” Dennis Banks, co-founder of the American Indian Movement tells me. “We need support from the music and art circles because there are not many Native people left in this country to create some kind of political clout. Cash did Bitter Tears in such a clever way that people were drawn into it without noticing that they were raising their shackles with us.” Bill Miller adds, “We can’t let our bitter history define us any longer” so we must cast aside these feelings that disconnect us and instead embrace a new movement. It’s a plea arising from the understanding that while the days of anguish may never stop, this and every creative-response possesses the power of telling real stories that can transform people and entire societies. So close your eyes. Wait. Listen. And then believe. Everything is possible.